A few years prior to Martin Luther’s fateful visit to Rome and his interrupted climb up the “Holy Stairs” he’d been a very promising student of law and philosophy. Martin’s father Hans had big plans for his eldest son and had spent a significant amount of money having him educated in law. There was no way Hans was going to have Martin follow in the family business of mining and was very insistent in pushing Martin towards a more prestigious line of work.

On a summer’s Sunday morning, as the twenty-one-year-old Martin set off from the family home to return back to his university studies in Erfurt, the future Reformer should have been paying more attention to the ominous weather on the horizon. A thunderstorm was gathering, but Luther’s thoughts were preoccupied with dissatisfaction over his studies. Like all university students have done for centuries, Martin wondered if his chosen degree was the right path to take.

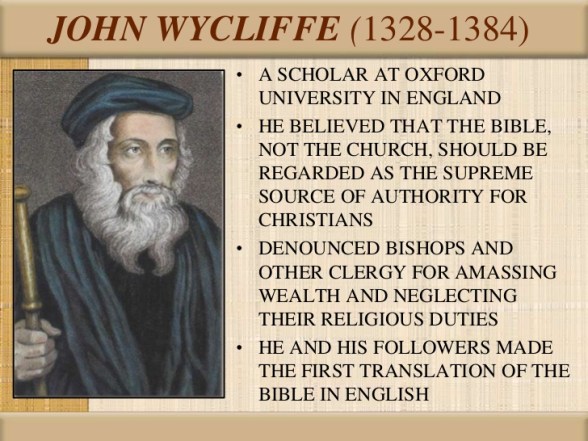

Martin had been thinking about changing his degree to theology, but how would he tell his father of these possible plans? The young Luther remembered his recent experience in the university library where he’d chanced upon a Latin Bible hidden away in the library’s recesses. He’d heard sections of scripture read in church but this was the first time Martin had held a Bible in his own hands. That experience of holding God’s Word had so excited him he’d wondered if there would ever be a day he would have his own copy. So it’s ironic that history would later record the future Doctor Martin Luther as translating the Bible into the German language and changing the political and spiritual landscape of Europe for the next five hundred years.

Martin’s thoughts were punctuated that Sunday as he noticed the lightning for the first time. The increasing volume told him the storm was heading towards him and so the promising university student sought shelter under a nearby tree.

But this would be no passing shower. The ensuing thunderstorm so petrified Martin Luther that when a nearby lightning strike shook the ground around him. Martin cried out desperately to Anna, the patron saint of miners – “Help me, Saint Anna!” So terrified of dying was Martin Luther he vowed that if he lived he would leave university and become a monk.

Two weeks later, Martin Luther stood by the door of the St. Augustine Monastery of Erfurt. A couple of university friends stood beside him still trying to talk him out of his decision. Surely Saint Anna understood that a hasty vow made in mortal fear wasn’t binding.

Martin knocked on the monastery door and asked to be let in. His parting words to his worried friends would be: “This day you see me, and then, not ever again.”

Martin Luther was wrong. His friends would see him again, and so would the books of history. One lightning bolt had changed the world.